The ISS seems fine after a Russian weapons test blew up a defunct satellite, but these incidents could become more common.

Russia shot down one of its Soviet-era satellites in a weapons test on Monday, sending more than 1,500 pieces of trackable debris into space. This forced astronauts on the International Space Station to shelter for about two hours in two spacecraft that could return them to Earth in the event of an imminent collision. While the ISS appears to be in the clear for now, experts say the situation is still dangerous. Satellite operators will likely need to navigate around this new cloud of space junk for several years and possibly decades.

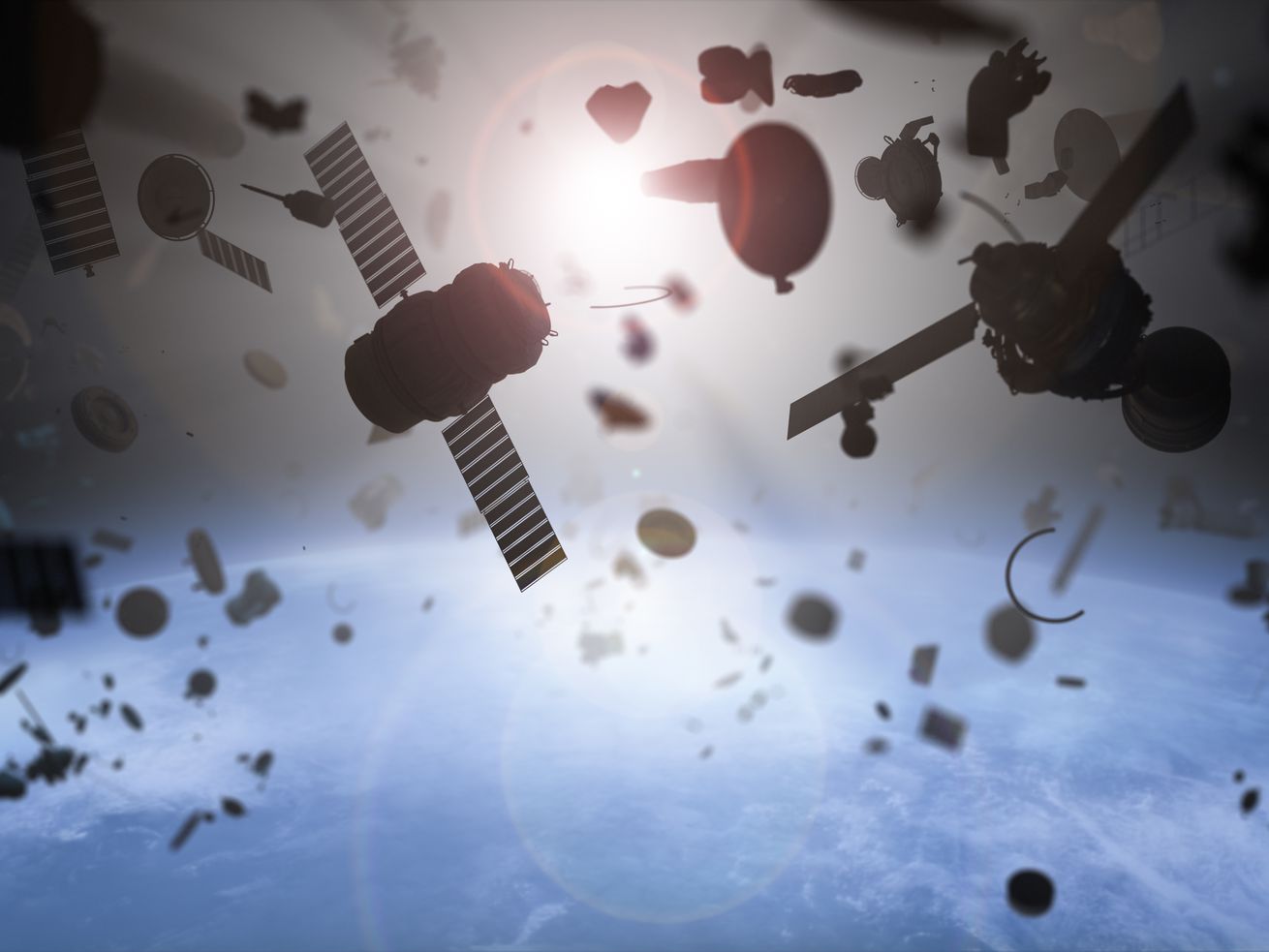

In fact, Russia’s latest missile test may have increased the total amount of space junk, including discarded pieces of rockets and satellites in Earth’s orbit, by as much as 10 percent. These shards are spinning at incredibly fast speeds and risk hitting active satellites that power critical technologies, like GPS navigation and weather forecasting. Space debris like this is actually so dangerous that national security officials are worried it could be used as a weapon in a future space war. In fact, the State Department has already said the Monday missile test is evidence that Russia is more than willing to create debris that jeopardizes the safety of all countries operating in low-Earth orbit, and even risks disrupting the peace in space.

These risks have only heightened concerns that we’re far from solving the space junk problem, especially as private companies and foreign governments launch thousands of new satellites into orbit — inevitably creating even more space junk.

Monday’s events, however, were more politically fraught than your average space debris incident. The Russian government launched a so-called antisatellite test (ASAT), which, as the name implies, is designed to destroy satellites in orbit. Launched from a site a few hundred miles north of Moscow, the missile struck a non-operational Russian spy satellite called Kosmos-1408 that had been orbiting the Earth since 1982. The satellite has now been broken into thousands of pieces that are currently whizzing around Earth at about 17,000 miles an hour, passing the International Space Station approximately every 90 minutes. While astronauts no longer need to shelter, the threat to the ISS or other satellites has not gone away.

“I’m outraged by this irresponsible and destabilizing action,” NASA administrator Bill Nelson said in a statement. “With its long and storied history in human spaceflight, it is unthinkable that Russia would endanger not only the American and international partner astronauts on the ISS, but also their own cosmonauts.” Nelson added that Russia’s actions were “reckless and dangerous” and also imperiled those aboard China’s Tiangong space station.

While Russia admitted to destroying a satellite in the recent test, its defense ministry insisted the event did not put the ISS at risk.

Russia is one of four countries, including India, the US, and China, to blow up its own satellite using an antisatellite missile. This trend is alarming because governments with ASAT systems could use the tech to attack other countries’ satellites, turning space into a battlefield. But even if countries only target their own space objects, Russia’s missile test shows how governments can also use anti-satellite missiles to create debris that endangers every country, company, or person operating in orbit. And again, once this debris is created, it can remain a threat for years. Just last week, the ISS had to adjust its altitude by about a mile to avoid hitting space debris from a satellite that China shot down in 2007.

The space junk problem is only getting bigger, too. Right now, there are more than 100 million pieces of space trash larger than a millimeter orbiting Earth, according to NASA. And as of May, the Department of Defense tracked more than 27,000 larger pieces of orbital debris, but even smaller pieces can still pose a massive danger to other satellites and space stations because of the incredibly high velocity at which they travel.

“I don’t think you can overstate the danger of space debris at this point,” Wendy Whitman Cobb, a professor at the US Air Force School of Air and Space Studies, told Recode. “As you create more debris, the chances of that debris hitting other things and creating more debris kind of just grows.”

What makes the space junk problem especially difficult is that no one has taken responsibility for it. According to the Outer Space Treaty, the foundation of international space law, countries remain the proprietors of whatever objects they send into space, so Russia still technically owns all the satellite fragments created by its Monday missile test. There isn’t a global consensus on what the penalties for creating space junk should be, and tracking and attributing different pieces of debris to different countries’ space operations is still difficult.

Government agencies and private space companies are developing technology to remove space junk, like nets that could catch debris in orbit and devices that would push satellites into the atmosphere to disintegrate. But there’s concern that governments could use the very same tools to take down another country’s satellites. At the same time, the cost of creating space junk — and removing it — is rarely factored into the decision to launch a vehicle or satellite into space.

“In a lot of ways, this is the same type of problem, an environmental issue that we’ve been dealing with on Earth in many, many forms,” Akhil Rao, an economist at Middlebury who has studied space debris, told Recode. “We’ve struggled with fisheries collapse, we’ve struggled with atmospheric pollution, [and] we’ve struggled with ozone depletion.”

Right now, the best way we have right now to ameliorate the many risks of orbital debris is to not create space junk in the first place. That might happen through better international cooperation or creating new economic incentives for private companies, but the sooner it happens, the better. While we’re generally able to navigate around the space junk that already exists, that will get more and more difficult as more debris builds up. And if we don’t figure out a solution in time, we could end up in a situation where low-Earth orbit is so packed with space trash that it’s unnavigable.

Post a Comment